At Bunter Spring, we strive to make wines that are delicious, interesting, and unique, using as few additives and preservatives as possible. We are convinced wine made this way not only causes fewer headaches, hangovers, and bad reactions, it also tastes better! Balance is of utmost importance. That means a pleasant and harmonious combination of alcohol/ sweetness, acidity, and astringency/tannin. Aroma and flavor are obviously important. We achieve interesting flavorful and balanced wines by using grapes grown carefully, in the right places, harvested at the right time. We prefer not to use additives, like oak chips, enzymes, tannins, grape concentrate or polysaccharides. But anyone who claims their wine is not manipulated at all, that they don’t intervene with the natural process in any way, is fooling you, or at least themselves. Nature, unhampered, turns grape juice into something resembling vinegar, or worse. If all we do is protect the wine from oxidation and spoilage then preserve it, for a time, by bottling, we have intervened plenty.

Originally, we declared we did not use high technology. Then came 2014, a year in which our dalliance with unsulfited “natural” wines resulted in several wines that, to be honest, had some problems, thanks to uncooperative microorganisms. Since our first duty is to make wine that tastes good, we successfully used “reverse osmosis” to treat the high ethyl acetate (smells like fingernail polish remover) and acetic acid (vinegar!) levels in several of the wines. Although this was somewhat of a moral dilemma, bottling and selling you bad wine was not an option. You deserve good wine and you deserve to know what you are drinking. We list what ingredients and techniques were used and how much sulfite is in the wine right on the label- every wine, every bottle. Incredibly enough, no one else does that. It seems most wineries believe you can’t handle the truth. Maybe they are embarrassed to tell it.

Our wines are not treated to make them heat or cold stable. If chilled, especially if accidentally frozen, they may precipitate some potassium bitartrate, harmless white flakes or crystals also known as cream of tartar, used in baking. If heated, they may get cloudy, but by then, the wine’s flavor is already ruined, so who cares?

In sunny California grapes often ripen with high sugar content, and that means the wines can have higher alcohol than we would prefer. We try, not always successfully, to keep the alcohol under 14%. We do this by harvesting grapes at less than 24% sugar by weight (24 degrees Brix). Sometimes we add a little water to the crushed fruit before fermentation, especially if hot weather had dehydrated the grapes prior to harvest. By law, we can’t reduce the Brix below 22.5. In practice, adding more than about ten percent water will have a negative impact on the wine. To minimize any dilution, immediately after crushing, before much flavor or color has been extracted, we will drain the calculated volume of juice from the must and replace it with the water. If we do add water, we list it as an ingredient. Obviously, this is something we strive to avoid, but nature, and grape growers, don’t always cooperate with our schemes. Water addition at crush (amelioration) or mechanical dealcoholization (spinning cone or R.O. and water addition) are very widely practiced here, but seldom admitted.

Another result of California’s warm summer weather is that grapes may be low in acid and/or high in pH. California winemakers commonly add tartaric acid, the primary acid naturally occurring in grapes, to raise acidity and lower pH. We sometimes do this, although it seems questionable to claim a wine is the expression of the vineyard when we have altered one of its most fundamental vineyard-derived characteristics. We reluctantly add acid if the wine would be flat-tasting or unbalanced without it. We don’t add just to hit a desirable “safe” pH level, so the pH of our wines still varies as a function of vineyard, variety, and vintage. Again, if we add acid, we say so on the label.

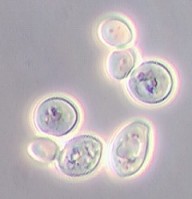

Yeast is essential to winemaking. Fortunately, or not, it occurs almost everywhere. It’s so small (20 million would fit on a quarter) it can float around in the air. Vineyards and wineries are well coated with a variety of species. Certain yeast can produce high levels of acetic acid (vinegar) and unusual aromas and flavors. To achieve a predictably palatable product, most wines are made with specially selected commercial yeast and, for wines that undergo malolactic (secondary) fermentation, commercial bacteria. At Bunter Spring, sometimes we add yeast, sometimes we don’t- the label will specify. We add yeast if the grapes skins are damaged by weather, insects, birds or fungus, and we suspect there is a high population of undesirable microorganisms. Whenever it seems a reasonable risk, we allow the “wild” yeast to do the job. We don’t usually inoculate with malolactic bacteria, but permit the ones resident in our barrels to do as they will.

We put sulfur dioxide (SO2, sulfite) in most of our wines. Sulfur dioxide is a widely used antimicrobial and antioxidant food preservative. We use moderate amounts, and the level present at bottling is shown on the label, or on the wine’s description on this website. Even if we don’t add any, a small amount is present, a byproduct of yeast metabolism. Very few people have any serious adverse reactions to the levels normally found in wine. Total SO2 (sulfite) in our wines is generally 30 to 100 parts per million (ppm). The legal limit is 350 ppm.

We don’t normally fine or filter our wines. Some feel filtration hurts a wine. We think that all depends, but we try to avoid it especially in the reds.. Fining agents typically settle out and are not present in the bottled wine, but we’ll still tell you if we added any. If we use any other additives, you guessed it, we’ll list them on the label, or on this website. By voluntarily listing all ingredients and processes, we avoid having to explain how “natural” our wine is or isn’t. Quality and drinking pleasure always come before our ideology- we try to do as little as possible, but we’ll do as much as is necessary to make sure you get a good bottle of wine. There’s no excuse for bad wine.